Hey, the Times is also doing a narrative about the Supreme Court hearing:

Alito suggests there are not enough legal safeguards in place to protect presidents against malicious prosecution if they don’t have some form of immunity. He tells Dreeben that the grand jury process isn’t much of a protection because prosecutors, as the saying goes, can indict a ham sandwich. When Dreeben tries to argue that prosecutors sometimes don’t indict people who don’t deserve it, Alito dismissively says, “Every once in a while there’s an eclipse too.”

If you are just joining in, the justices are questioning the Justice Department lawyer, Michael Dreeben, about the government’s argument that former President Trump is not absolutely immune from prosecution on charges that he plotted to subvert the 2020 election. Dreeben has faced skeptical questions from several of the conservative justices, including both Justices Alito and Kavanaugh, who have suggested that the fraud conspiracy statute being used against the former president is vague. That statute is central to the government’s case against Trump.

Justice Alito now joins Justice Kavanaugh in suggesting that the fraud conspiracy statute is very vague and broadly drawn. That is bad news for the indictment brought against Trump by Jack Smith, the special counsel.

The scope and viability of this fraud statute, which is absolutely central to the Trump indictment, wasn’t on the menu of issues seemingly at play in this hearing. Kavanaugh and Alito appear to have gone out of their way to question its use in the Trump case.

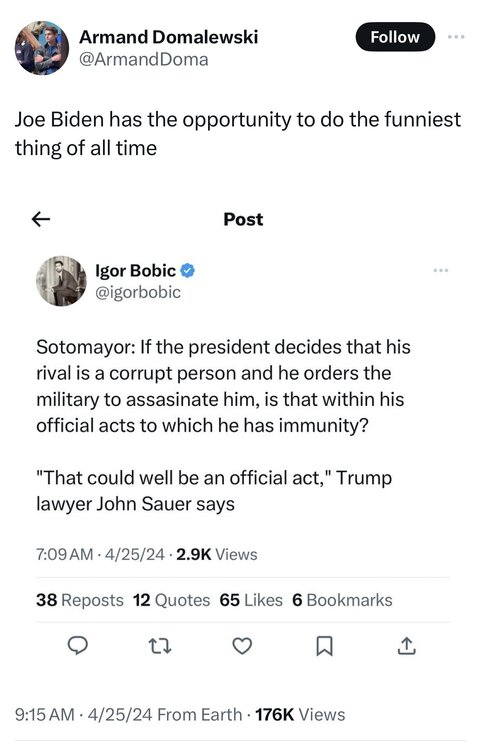

Justice Sotomayor points out that under the Trump team’s theory that a criminal statute has to clearly state that it applies to the presidency for it to cover a president’s official actions, there would essentially be no accountability at all. Because only a tiny handful of laws mention the president, that means a president could act contrary to them without violating them. As a result, the Senate could not even impeach a president for violating criminal statutes, she says — because he would not be violating those laws if they don’t apply to the president.

Dreeben is under heavy fire from the court’s conservatives.

Justice Gorsuch is questioning Drebeen directly on whether another key charge against Trump — an obstruction statute — should apply to Trump’s alleged disruption of the certification of the election. The court held a hearing earlier this month on whether that obstruction law should be applied to members of the pro-Trump mob that attacked the Capitol on Jan. 6. Trump was never mentioned in that hearing. But now the use of the obstruction law against Trump has come up.

Dreeben says there are some core constitutional functions of a presidency — he cites the pardon power, the power to recognize foreign nations, the power to veto legislation, the power to make appointments — that Congress cannot regulate and so criminal statutes cannot be applied to such actions. Justice Gorsuch declares that is essentially immunity for some official acts.

Justice Kavanaugh just dropped a bit of bombshell, saying that the main fraud conspiracy statute Trump has been charged with in this case — 18 U.S.C. 371 — is written so vaguely that an aggressive prosecutor could use it against future presidents in a very broad way.

Dreeben argues that the Constitution has explicit textual immunity for legislative acts by members of Congress (the Speech and Debate clause) because there had been an historical example of legislators being harassed and prevented from doing their jobs. The framers of the Constitution did not put anything like that in for presidents, he argues, because they had a very different concern — after rebelling against the British king, one of their chief concerns was the risk of presidential misconduct.

Overall, several justices — maybe a majority — apear to have suggested through their questions that presidents should indeed enjoy some level of immunity from criminal prosecution. The questions seem to be how to decide what actions are protected from criminal charges and whether the allegations in Trump’s indictment in particular would qualify for immunity.

Justice Thomas cites “Operation Mongoose” in asking why no ex-presidents have been charged in the past. That is an odd example. President John F. Kennedy ordered Operation Mongoose — a covert operation in Cuba. Of course, Kennedy never had an opportunity to be an ex-president.

An exchange with Sauer a few minutes ago and now Dreeben’s opening statement gets at a central question: is the fact that no ex-president was charged with a crime before Trump evidence that presidents have always been understood to be immune, or is it evidence that there are layers of protection against abusive or politicized prosecutions of ex-presidents who did not really commit crimes like Trump allegedly did?

Michael Dreeben, speaking for the government, lays out his bottom line. Executive immunity would license a president to commit “bribery, treason sedition, murder” and, as in Trump’s case “conspiring to use fraud to overturn the results of an election and perpetuate himself in power.”

“The framers knew too well the dangers of a king who could do no wrong,” Dreeben says.