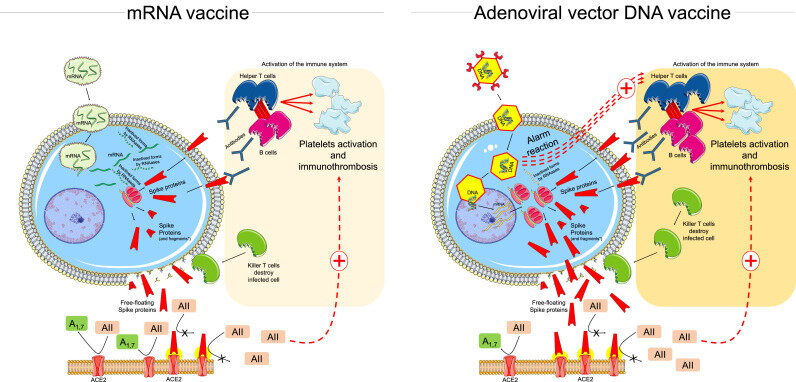

This is the subject of multiple studies right now. Preliminary evidence out of the UK suggests that mixing and matching the different technologies (mRNA [Pfizer, Moderna], adenovirus vector [J&J, Astrazeneca], and subunit vaccines [Novavax]) might drive a better and longer lasting immune response compared to sticking with one company. This makes a lot of sense because the different technologies are going to stimulate different cell signaling pathways. For example, mRNA mechanisms are better at stimulating the B-cell driven antibody response whereas the adenovirus vector vaccines are going to do a better job at building cellular (T cell) immunity.

It probably won't hurt you (we don't have large controlled trials to be sure), but I don't think you will really benefit much.

Right, I'm not against boosters, but breakthrough cases are not the metric I'm looking at. The outcome of those cases is the key metric. As long as the vaccine is preventing severe disease (which it is) I don't see much reason to get a booster. And as I've outlined in prior posts there might be advantages to waiting and see how more experiments and trials play out before deciding when to get boosted and which shot to take.

There is precedent for using infection outcomes rather than infections themselves in our recommended vaccine schedule. Pertussis (whooping cough) used to kill thousands of infants. In the 1930's a vaccine was developed by killing whole pertussis cells and injecting them into people. It worked well, but because of toxins normally found in the bacteria that were not affected by the inactivation, a small number of people had significant side effects after vaccination. This lead to the development of the modern day Pertussis vaccine, the acellular Pertussis vaccine (aP), which is found in the combination TDaP and DTaP vaccines. This vaccine injects a small amount of the actual protein responsible for all the horrible symptoms of whooping cough, thereby programming your immune system to essentially convert Pertussis from whooping cough into an asymptomatic bacteria that can live in your respiratory tract. Recent studies have shown that people (and monkeys) can transmit Pertussis, and might even be able to transmit it more easily than an unvaccinated person because they have no idea they are sick. This is why the Pertussis vaccine schedule is so aggressive, particularly in infants. They get shots at 2, 4, 6, 15 months, another one at age 4, and then intermittently from then on out and in pregnant women. This aggressive schedule, combined with antibiotics, are the reasons whooping cough deaths have remained incredibly low.