Uh you're a fucking lunatic, bro.

You know what's even more deadly than COVID and rabies? Flying an SR-71 in a combat situation. Trust me, as a former SR-71 pilot, and a professional keynote speaker, the question I'm most often asked is "How fast would that SR-71 fly?" I can be assured of hearing that question several times at any event I attend. It's an interesting question, given the aircraft's proclivity for speed, but there really isn't one number to give, as the jet would always give you a little more speed if you wanted it to. It was common to see 35 miles a minute. Because we flew a programmed Mach number on most missions, and never wanted to harm the plane in any way, we never let it run out to any limits of temperature or speed. Thus, each SR-71 pilot had his own individual “high” speed that he saw at some point on some mission. I saw mine over Libya when Khadafy fired two missiles my way, and max power was in order. Let’s just say that the plane truly loved speed and effortlessly took us to Mach numbers we hadn’t previously seen. So it was with great surprise, when at the end of one of my presentations, someone asked, “what was the slowest you ever flew the Blackbird?” This was a first. After giving it some thought, I was reminded of a story that I had never shared before, and relayed the following.

I was flying the SR-71 out of RAF Mildenhall, England , with my back-seater, Walt Watson; we were returning from a mission over Europe and the Iron Curtain when we received a radio transmission from home base. As we scooted across Denmark in three minutes, we learned that a small RAF base in the English countryside had requested an SR-71 fly-past. The air cadet commander there was a former Blackbird pilot, and thought it would be a motivating moment for the young lads to see the mighty SR-71 perform a low approach. No problem, we were happy to do it. After a quick aerial refueling over the North Sea , we proceeded to find the small airfield. Walter had a myriad of sophisticated navigation equipment in the back seat, and began to vector me toward the field. Descending to subsonic speeds, we found ourselves over a densely wooded area in a slight haze. Like most former WWII British airfields, the one we were looking for had a small tower and little surrounding infrastructure. Walter told me we were close and that I should be able to see the field, but I saw nothing. Nothing but trees as far as I could see in the haze. We got a little lower, and I pulled the throttles back from 325 knots we were at. With the gear up, anything under 275 was just uncomfortable. Walt said we were practically over the field—yet; there was nothing in my windscreen. I banked the jet and started a gentle circling maneuver in hopes of picking up anything that looked like a field. Meanwhile, below, the cadet commander had taken the cadets up on the catwalk of the tower in order to get a prime view of the fly-past. It was a quiet, still day with no wind and partial gray overcast. Walter continued to give me indications that the field should be below us but in the overcast and haze, I couldn't see it.. The longer we continued to peer out the window and circle, the slower we got. With our power back, the awaiting cadets heard nothing. I must have had good instructors in my flying career, as something told me I better cross-check the gauges.

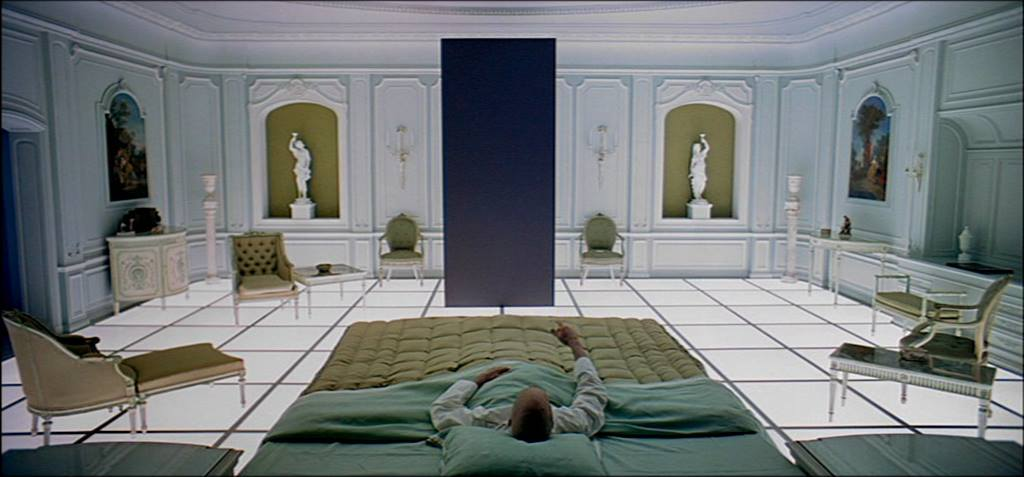

As I noticed the airspeed indicator slide below 160 knots, my heart stopped and my adrenalin-filled left hand pushed two throttles full forward. At this point we weren't really flying, but were falling in a slight bank. Just at the moment that both afterburners lit with a thunderous roar of flame (and what a joyous feeling that was) the aircraft fell into full view of the shocked observers on the tower. Shattering the still quiet of that morning, they now had 107 feet of fire-breathing titanium in their face as the plane leveled and accelerated, in full burner, on the tower side of the infield, closer than expected, maintaining what could only be described as some sort of ultimate knife-edge pass. Quickly reaching the field boundary, we proceeded back to Mildenhall without incident. We didn't say a word for those next 14 minutes. After landing, our commander greeted us, and we were both certain he was reaching for our wings. Instead, he heartily shook our hands and said the commander had told him it was the greatest SR-71 fly-past he had ever seen, especially how we had surprised them with such a precise maneuver that could only be described as breathtaking. He said that some of the cadet’s hats were blown off and the sight of the plan form of the plane in full afterburner dropping right in front of them was unbelievable. Walt and I both understood the concept of “breathtaking” very well that morning, and sheepishly replied that they were just excited to see our low approach. As we retired to the equipment room to change from space suits to flight suits, we just sat there-we hadn't spoken a word since “the pass.” Finally, Walter looked at me and said, “One hundred fifty-six knots. What did you see?” Trying to find my voice, I stammered, “One hundred fifty-two.” We sat in silence for a moment. Then Walt said, “Don’t ever do that to me again!” And I never did. A year later, Walter and I were having lunch in the Mildenhall Officer’s club, and overheard an officer talking to some cadets about an SR-71 fly-past that he had seen one day. Of course, by now the story included kids falling off the tower and screaming as the heat of the jet singed their eyebrows. Noticing our HABU patches, as we stood there with lunch trays in our hands, he asked us to verify to the cadets that such a thing had occurred. Walt just shook his head and said, “It was probably just a routine low approach; they're pretty impressive in that plane.” Impressive indeed. Little did I realize after relaying this experience to my audience that day that it would become one of the most popular and most requested stories. It’s ironic that people are interested in how slow the world’s fastest jet can fly. Regardless of your speed, however, it’s always a good idea to keep that cross-check up…and keep your Mach up, too.